Wednesday, March 25, 2009

Lists, Lists and More Lists

Walker:

Hybridity

Appropriation

Performance

Space

Time

Felicie:

Respect

Dissolution

Inclusion

Engagement

Jennifer:

Succession

Exploration

Displace

Sensitivity

Process

Gene:

Structure

Function

Process

Driving force

Sustainability

David:

Pasear (walk)

Estampa (to make a mark)

Colonizacion

Poner la bandera (plant flag)

Enmarcar (Frame the landscape)

Recordacion (Memory)

Final List:

Dissolve

Enmarcar (Frame)

Engage

Relolectar (Recollect)

Witness

Saturday, March 21, 2009

belated week one and two

Hello from california. So sorry that I have not posted over the past couple of weeks. I have been reading and thinking and writing, but just have not found the time to compose a few paragraphs. it has been a particularly busy month.

Back to Bill Fox’s first question about appropriating terminology… My work often crosses over into the fields of architecture, urban planning, sociology, etc—all fields in which I have never had serious academic training. The wonderful thing about coming to these related issues as an artist, rather than an academic grounded in a specific field, is that I am able to re-frame these terms, placing accepted truths in new contexts, with new interpretations. As an artist I feel quite comfortable borrowing terms from a variety of disciplines, I can mash them together, put them in a different light. These “borrowed” terms” not only inform the way we make/articulate artwork; in an ideal situation, our appropriation can also inform the way those academics use their own terms too, actually expanding definition and context for them. I teach in a liberal arts college, and to me it is incredibly important that the arts remain the hub of the liberal arts, rather than an adjunct department off to the side. At Oberlin, more students pass through art classes from other departments than most any other department on campus, so we are constantly seeing the infusion of many varied lingos and contexts into our students’ paintings and sculptures and net art. The creative process of re-working ideas and putting them in new contexts is central to the arts––and increasingly, the artists’ re-imagined use of these terms and ideas is becoming integral to the development/progress in other fields. I had an environmental studies student last semester make a sculptural visualization of some principles she had been studying in her environmental economics class, an experience that deepened her own understanding not only of what art can be, but what economics can be. http://youwillneverfind.us/landarts/exhibit/margaret

On to week two---In terms of hybridity… Again, I think of my students. I am reminded every day that they learn in a different way than I did when I was in school, simply because they have grown up in a dramatically more hybridized world, and many of the creative tools that I use in my art practice have been a part of their lives since they could sit at the computer. I will be emphatic about the impact of a networked culture, a google culture, a facebook culture. And they shrug and remind me that they started their first blog when they were in 6th grade, a few years after they learned to use digital cameras, Final Cut Pro, their iPod, their first cell phone. Often I am invited to take part in conferences or symposiums about digital arts and the institution, questioning how museums and colleges are changing in light of digital/media/hybrid arts. And I generally feel like it would have been important to include a few 20 year olds in those conversations. When I am talking about integrating digital media into say, my tenured painting friend’s painting class, I often feel like I am explaining to her how she can use digital media, not how a kid-who-has-used-the-internet-since-the-age-of-3 can use the media. Which can lead to some circular conversations. Same with hybridity. My college students cross over between the silos on campus so fluidly, their painting projects intersect with my electronic music classes and their economics with my "land arts in an electronic age" class, while the institution is scratching its head.

All to say: I am excited for the future, cant wait to see how things change when these 20 year olds start taking part in these conversations. (This conversation that we are having on this blog, is, by the way, totally interesting and compelling, and I am not saying it is not worth having these conversations. I just think my students are having a very different version of this conversation, and I learn a lot from them too.)

Tuesday, March 10, 2009

Response to Week 1 provocation

First of all, sorry to respond to Bill Fox’s week one provocation so late in the game—I just launched a new Web-based project over the weekend, which has taken up most of my time & energy for the last few days.

In terms of borrowing “constructs and terms from science for the purpose of art & environment projects” I have been less interested in farming/appropriating scientific discourse and specific terms as my themes for my projects and more interested in illustrating scientific concepts for my audience to connect complex human/ecological relationships to a specific environment or area I’m studying and documenting.

For instance, when I began focusing (my camera) on the Salton Sea in the mid to late ‘90s, I realized that I could not show the images without some in depth explanation of what was depicted within them. (Foremost, it was important for me to understand this myself). A title or caption did not work, as it just didn’t really convey the complexity of the condition, the history, or even the humor/irony of a particular scene. Hence, writing became just as important as the photographic images in defining what was happening to these places.

For instance, when I began focusing (my camera) on the Salton Sea in the mid to late ‘90s, I realized that I could not show the images without some in depth explanation of what was depicted within them. (Foremost, it was important for me to understand this myself). A title or caption did not work, as it just didn’t really convey the complexity of the condition, the history, or even the humor/irony of a particular scene. Hence, writing became just as important as the photographic images in defining what was happening to these places.Consequently, I realized that I had to do my homework understand the biological and scientific terms and conditions I was seeing while working on site. Not trained in these fields I did a lot of reading and research. I began to seek out scientific resources such as the Dr. Victoria Matey and her late, husband, Dr. Borris Kuperman at SDSU who were imaging parasite infestations on tilapia found at the Salton Sea. (This non-native species suffered sporadic catastrophic die-offs throughout the ‘90s into the turn of the century and would cover the shore with thousands of rotting carcasses at various times). Matey and Kuperman’s published scientific findings showed that the infestation (a beautiful image in itself) was one of the many related environmental hazards causing the tilapia population to implode. (Tilapia is a prolific breeder and the population at the Salton has always managed to recover from die-offs).

I included some of the Matey/Kuperman scanning electron microscope from their Salton study in my book seeing them as beautiful aesthetic images and also a way to inform the viewer about biological systems/relationships within the sea. I guess I’m interested in ways artist projects can help relate scientific discourse visually or in some other creative way to an audience and still incorporate scientific rigor without making it as dry as can be when reading the same information in a textbook. Artists such as Mark Dion are really good at this. Perhaps there’s something that the scientific community can learn from us artists as well?

Week 1-Claude Glass

A while back I read Arnaud Maillet's "The Claude Glass" (Zone Books 2004) and it got me pretty excited about a simple use of optics and an early way of reading one's environs. The Claude glass was a dark piece of reflective material that an artist would hold in one hand while facing away from the landscape to be depicted. I imagined that this piece of magic collapsed the view onto a two dimensional surface and took away its color, making the tonal reading for which it was made. Thinking about it and then testing, it doesn't really work that way: not the easy way to make the world black and white I had expected. I began using the method though within installations, so that with every building move, there was also a reflection, an image of the three dimensional, often one that was scaled to include the observer.

In my last installation I used a black reflective material (big sheets of black plexi) as a flooring that that the viewer moved across to view a model of a landscape I had cast in the space. By the end of the installation the landscape model was repositioned and the flooring (now covered in the results of the casting process) hung vertically as a wall-like division in the space.

Accuracy Matters to Us

For the past three years we have been working exclusively on climate change. In this work, we aim for as little slippage as possible in our use of scientific or quasi-scientific terms. We recognize that we have no independent means by which to gauge the claims of the IPCC or any other scientific body with respect to perceived changes in global mean temperatures and the likely cause for this change (anthropegenic forcing from greenhouse gas emissions). We seek to confirm rather than subvert the authority of these scientific bodies. We would like, as much as possible, to use their langauge according to the rules of their language game.

Which is not to say we have no epistomological agenda. We consider our work research. We are very concerned with knowing the landscape and how we know it. We are concerned with the limits of this knowing and and are concerned to respect and inspire respect for those limits.

The photographs of our project (such as the one above of the mountain with vanished glacier) say nothing in and of themselves about climate change. They are like a blank stare. Only by placing them in context (the context provided by science and history) can we begin to penetrate that stare.

Where we have begun to appropriate material is in the use of imagery from various disciplines mostly ethnographic, archaeological and scientific. We are interested in understanding this present moment (so sudden and dangerous-seeming) as the culmination of various histories. We believe that we can only progress in this understanding by being comfortable with fragments and contradictions, complexity. (Even if in certain iterations of our project we banish such complexity).

This interest has led us to use images such as those above from the Peabody Musuem at Harvard. Like our original photograph, they from Peru. (Peru, which depends so heavily on the Andean glaciers that will be gone by the middle of the century).

Complexity and fractal algorithms

When I designed 'Heart of Reeds' in my home town I worked with ecologists to find a pattern which would give us the most likelihood of biodiversity. Given that we were designing the shape of land and water, the ecologists felt that the more 'borderlands' we could make, the more biodiversity we would get, so in effect I was drawing with islands. In the end I settled on a a double vortex complex pattern from the apex of a heart, where the pattern of the muscles is laid down in the pattern of the most efficient flow of blood. This in medical terms is a Cardiac Twist. Simplified this pattern, which symbolically connects us to nature, also provides what amounts to ribbons of islands.

2 Cardiac Twist drawings: blood and river mud on paper

The work was excavated in 2004, planted with reeds, one metre apart, and the vegetation which was there before, allowed to regenerate. It is managed for the benefit of biodiversity and the only plant which is discouraged is willow, to prevent woodland developing. In terms of wildlife it has been specacularly successful and there are many species which have colonised the land and water. It is teaming with life and this makes it a much loved place for people of the town.

I wonder if this complex pattern is also a fractal algorithm, since it is also found in river and weather systems and also the formation of galaxies. If you go up or down in scale similar patterns exist. Is this universal pattern of flow the most conducive to life?

Monday, March 9, 2009

theodolite

theodolite "the great grey greasy limpopo" magnifying plumb bob

theodolite "the great grey greasy limpopo" magnifying plumb bobthese three images all come from work about surveying. i borrow the terms and the objects and remake them into creatures of my own devising. the theodolite has a mirror and lens added to a basic sighting mechanism that allows a viewer to superimpose his/her own image on the landscape. the drawing shows the area adjacent to the limpopo river -- land my great-grandfather owned and ran cattle on which i have an ongoing proposal to do a perimeter walk and understand the changes in south africa as they read on this piece of land. the magnifying plumb bob is a measuring device altered to a viewing eyepiece, hung at foot level allowing a closeup view of the hands digging in video below the bob. the two brass pieces i made on a lathe and mill -- borrowing further the 18th century technologies of hand production. the map is hand drawn as well. so i borrow and transform past technology, seen as science at the time. surveyers in the 18th century were highly valued and highly rewarded. George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, both were surveyors and thus acquired land. the men who worked for them were not so lucky -- hard work and not much credit in wading swamps and throwing chains around.

just a thought on appropriation

provocation:1

ecol·o·gy

German Ökologie, from öko- eco- + -logie –logy

1: a branch of science concerned with the interrelationship of organisms and their environments

2: the totality or pattern of relations between organisms and their environment

3: human ecology

4: environment , climate , the moral ecology ; also : an often delicate or intricate system or complex, the ecology of language

I’d be interested in applying another of the terms supplied by our Walker contingent to the question. It seems to me that in the migration of scientific terms is the direct result of the current wave of trans-disciplinary collaboration that is happening in academia and the art world at large. The result is an inevitable Hybridity in which two or more disciplines bring their interpretations to any given term.

I have experienced this several times of late in my practice, one example being our project for Lucy Lippard’s Weather Report exhibition. For this show, artists were charged with finding a scientist with whom to partner in creating a work that addressed climate change. I put together a team at UNM consisting of myself, Erika Osborne, artist and colleague in the Land Arts of the American West program and Bruce Milne, biologist and head of Sustainability Studies. We also consulted with plant biologists at the US Forest Service station in Fort Collins, CO. The focus of the piece was to plant species at our chosen site at the National Center for Atmospheric Research that stood to prosper

over the long term as the climate warmed.

Central to the conception of the piece was the idea that our site was situated at an Ecotone (a scientific term) and would therefore demonstrate a significant and rapid change in plant community.

eco·tone:

ec- + Greek tonos tension — more at tone

1: a transition area between two adjacent ecological communities

The question I brought to Bruce Milne was what scientific principle could we use to define the planting plan to maximize our possibility of success. He suggested we apply a fractal (another scientific term) algorithm.

frac·tal ,

French fractale, from Latin fractus broken,

1: any of various extremely irregular curves or shapes for which any suitably chosen part is similar in shape to a given larger or smaller part when magnified or reduced to the same size

The resulting proposal that we submitted contains a planting plan with Erika’s drawing of our chosen native species that is based on the “bough” fractal. In the end, the work combines several scientific concepts/terms in an art piece. It’s a hybrid.

Scale

Hi Everyone,

I responded to Bill's provocation with a comment back to him. I probably should have responded with a "week one" post. Here's what I wrote:

It isn't really a scientific term, exactly, but the concept of "scale" and scale shifting comes up a lot in the introductions people have made to their work. Scientists investigate phenomena using microscopes and other technologies that shift the visual/aural/tactile/time/space scale. Artists have long appropriated these investigative technologies. In our own group, just to pick a few examples, Chris's juxtaposed scales-- echogram and echocardiogram--call attention to each and invite us to consider the relationship between them. Julia's BigBoxReuse (I love this project) documents the scale shift as communities take over nationally-based, large scale buildings and turn them to local, community-based uses. The Canary Project tracks the time-scale of climate change. . . .

In my own work, I would love to be able to acquire a scientific instrument that would allow me to take very thin cross-sections of plants in order to use those in my films. I'm using much cruder kitchen and artist tools to achieve these results now. Such science lab instruments are prohibitively expensive or potentially contaminated, from what I understand. I realize I'm talking about appropriating tools rather than concepts, but this is where I am.

entropic attractions

Sunday, March 8, 2009

appropriating the "limit case"

Thanks to Bill for a great provocation for this week ... I'd like to respond to his invitation to:

"hear a bit about how any of us have borrowed constructs and terms from science for the purpose of art & environment projects, and how we’ve bent them to our purposes. In short, instead of arguing about whether we’re using a scientific concept correctly or not, I’d like to propose that it may not matter--that, in fact, it’s the entire point to not use the word or concept in the same fashion as a scientist. That’s a mechanism typical of a living language, hence a culture."

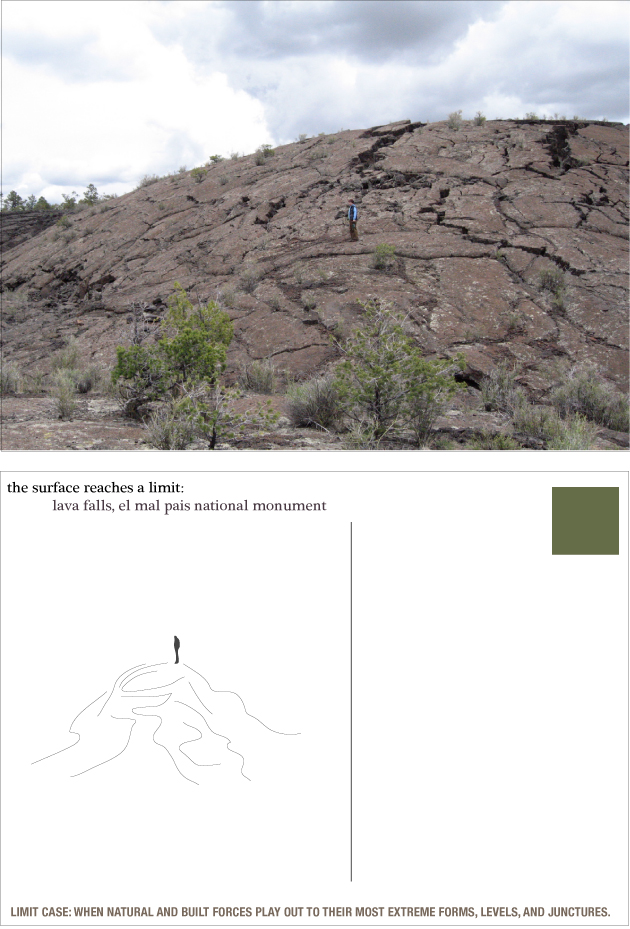

In 2007, smudge studio (Jamie Kruse and I) appropriated the term "limit case" from calculus and used it for the purpose of an art + environment project called the "Limit Case Postcards." In calculus, as far as I can make it out, "limit case" refers to the point at which "we have gone as far as we can go within the terms of a particular theorem." It addresses the question: What is happening to a function as it approaches a certain point?

I really don't understand calculus at all. But while on a research and art-making trip, we were drawn to the phrase "limit case' because it somehow captured the force and energy of the landscapes, land uses, and extreme social environments that we were passing through. We decided that we would respond to our experiences by making what we called "limit case postcards." Here is our artist statement:

We traveled through the American southwest for 28 days.The trip consisted of 3700 miles (a figure 8 of sorts). We selected sites that would offer us experiences of intensity: intensity of landscape, color, climate, remoteness, shape, history, and site-responsive built environments. We found ourselves arriving at sites where humans, the landscape and the built environment converged to create exquisitely concentrated zones of contact. State borderlines converged with deep economic divisions; remote desert "wasteland" converged with garish tourist attractions; a quonset hut used to develop the atomic bomb converged with present day efforts to redesign it for sustainable living practices in the desert.

The experiences compounded and we began to regard such moments as "limit cases": intense points where natural and built forces mutually contaminate as they play out to their most extreme forms, levels, and junctures. The postcards visualize sites reaching their "limits" and passing into something else.

Bill's provocation resonated for me because as you can see in the artist statement, we took great liberty with the idea of a "limit case" when we used it to help us visualize what it felt like to us to encounter natural and built forces as they reached their most extreme forms, levels and junctures and passed into something else.

I'm not sure if our sense of "limit case" is at all close to what mathemeticians call limit cases ... but our appropriation of these words and as much of the concept as we could grasp helped us immensely in finding some language to express what was otherwise difficult to describe in words. Here's one of the post cards that resulted:

Saturday, March 7, 2009

Digital entropy

A couple of weeks ago a most incredible image of a rock was posted on the BLDG BLOG.

I ended up not paying much attention to the content of the post, but was struck by how much I enjoyed encountering this image online. I realized how rare it is to see such a clear piece of the natural environment existing within the virtual- and how encountering it online simultaneously altered my habitual experience of the virtual, as well as of the natural. Ironically, I have taken the time to look more closely at a rocks since finding this image.

It made me think further about the work of Robert Smithson and what might be an example of "digital entropy" today. I'm just starting to think about this, but for the purposes of this conversation I thought I would give it a try.

click image to enlarge to full-size

Friday, March 6, 2009

write/erase/ap/prop/ri/ate/appropriation

My gaze was caught by a site-specific 9,000-year-old rock painting of a woman wearing a skirt and lying on her side painted as a “hole” in her body. Scholarship into the history of the Paint Rock site located near Junction, Texas, failed to note a faint voice bubble issuing from her mouth, creating a paradox in interpretation: why had a white female captive (according to scholars) been given a voice at that time? I used this sight/incite to call attention to the erased cultural memory of women’s contributions to society by filling the “hole” (symbolically a water bowl in her womb) with water so that viewers could dampen a cloth and erase another’s history written on the stones at her feet, and then write their own stories on the stones. In this way, my artwork connects the history of a woman painted at Paint Rock to contemporary issues of women’s erased cultural memory, thus providing a palimpsest of the pictograph that “floats” simultaneously with each and every erasure to (re)create a fresh historical trace concerning this continuous erasure of women’s contributary cultures.

Cloud Chambers and Strange Attractors

\

\Thursday, March 5, 2009

March 5-12, 2009